Early morning last week…a drone took off over Hambledon after light snow. Perfect conditions, the snowflakes had settled into the valleys of the great encircling hillfort ditches… and streets of round house platforms became visible as rows of hollows outlined in white.

Hambledon Hill light snow shows the dimples where Iron Age round houses once stood.

These photos help illustrate the majesty and awe of this vast archaeological site and has helped us launch the National Trust’s Wessex Hillforts and Habitats project. With the help of Marie, our project officer, the People’s Postcode Lottery have granted over 100,000 pounds to get the project started.

The primary purpose of the project is to enhance the conservation of 13 NT Iron Age hillforts scattered across Dorset and South Wiltshire …but it will also inspire people to get involved and to carry out monitoring and research. It will also create new interpretation to bring these grassy hill top earthworks to life as places to be appreciated, valued and better understood. Alongside this.. to highlight nature, particularly the plant and insect life. Each hillfort’s unique topography nurtures precious habitat undisturbed by agriculture for over 2000 years.

Purple spotted orchids growing on the sheltered slopes of a hillfort ditch

So.. where are these places. I’ll list them out for you…. and as some have featured in previous blog posts I’ll reference these while we have a quick tour.

We’ll start in Wiltshire and from there head south and west and eventually end at the Devon border.

Figsbury Ring, north-east of Salisbury. A circular rampart and ditch with a view back to the great cathedral spire. Strangely, Figsbury has a wide deep ditch within the hillfort ..potentially Neolithic but there is no rampart.. where did all the chalk go?

Figsbury Ring from its rampart top showing the wide deep ditch inside the hillfort.

South of Salisbury, Wick Ball Camp above Philipps House, Dinton.. NT only owns the outer rampart.

Then there is the icon of Warminster, Cley Hill (blog posts “Upon Cley Hill’; Upon Cley Hill 2”), a flying saucer shaped chalk outlier with two round barrows on the summit..a strange hillfort.

To the south west, at the source of the mighty River Stour, is the Stourhead Estate with its two hillforts. These are Park Hill Camp, its views hidden by conifer plantation and Whitesheet Hill (blog Whitesheet Hill Open at the Close) with wide prospects across the Blackmore Vale towards Hambledon and Hod. We’ll follow the Stour to reach them.

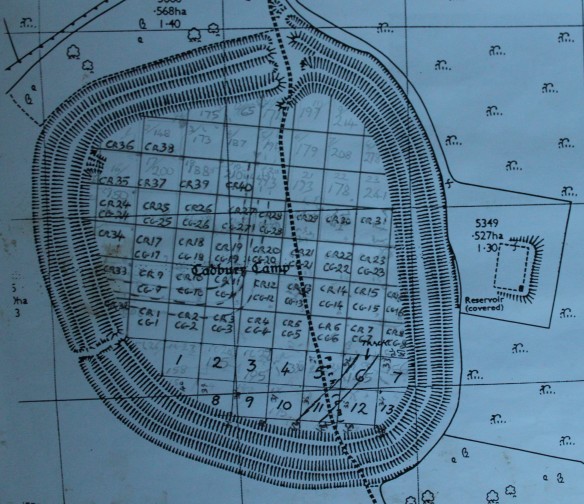

Hod is the largest true hillfort in Dorset, the geophysics has shown it full of round houses…a proto town… and there are the clear earthworks of the Roman 1st century fort in Hod’s north-west corner (blog post Hod Hill Camp Bastion)

Hambledon is close by, just across a dry valley, perched high on a ridge, surrounded by the Neolithic, you feel like you’re flying when standing there. (blog post Archaeology SW day 2014, Hambledon Sunset)

Follow the Stour further south and you reach the triple ramparts and ditches of Badbury Rings on the Kingston Lacy Estate. From here you can see the chalk cliffs of the Isle of Wight (blog post Badbury and the Devil’s footprint)

Now from Badbury take the Roman road west to Dorchester and keep going beyond the county town, glancing at Maiden Castle as you pass(Duchy of Cornwall, English Heritage).

The Roman road continues straight towards Bridport but branches from the A35 road before you reach the village of Winterbourne Abbas.

It has now become a minor road.. a couple of miles on… it branches again..still straight but this once arterial Roman route to Exeter has dwindled to a narrow trackway with grass sprouting from the tarmac.

Don’t lose heart…keep going…and you will break out onto the chalkland edge and the multiple ramparts of Eggardon Hill.

From Eggardon, the other hillforts emerge as sentinals ringing the high ground overlooking the Marshwood Vale, and, to the south, the cliffs of Golden Cap.. and beyond, the sweep of Lyme Bay and the English Channel.

Next to the west is Lewesdon Hill, a small fort but occupying the highest land in Dorset, nearby is the second highest, the flat top of Pilsdon Pen, surrounded by double ramparts and enclosing Iron Age round houses, Bronze Age round barrows and the pillow mounds of the medieval rabbit warren.

The last two in the Project guard a gap through the Upper Greensand ridge at the Devon border. Coney’s Castle has a minor road running through it and on its south side are wonderful twisted moss covered oaks… and beneath them the deep blue of bluebells in the Spring. Lambert’s Castle was used as a fair up to the mid 20th century, remains of the fair house and animal pens can be seen there ….but once again the views are spectacular, particularly in early morning after frost with the mist rising from the lowland.

Lambert’ s Castle after frost.

Lambert’ s Castle after frost.

A baker’s dozen of hillforts of the 59 the NT looks after in the South West.

One might imagine that these huge works of humanity look after themselves… but they need to be cared for.. we must have farmers willing to graze the right number and type of stock on them….at the right times; NT rangers and volunteers to cut regenerating scrub and fix fencing and gates…

If not, these nationally important scheduled monuments and SSSIs will deteriorate. The earthworks will become overgrown and grassland habitat will be lost, archaeological knowledge locked in the layers beneath the soil will become disrupted… and the views into the landscape and across and within the hillforts will become hidden.

The Wessex Hillforts and Habitats Project promises to be an exciting time of conservation and discovery. The work has now begun!