National Trust South Somerset has some great buildings and most have featured in this blog over the years.. but, for some reason, Lytes Cary has been forgotten.

Quite surprising really because it is a wonderful place.

The manor house is a fine combination of local blue-grey lias stone and Ham stone which was used for its door and window openings.. a slightly less local golden brown stone

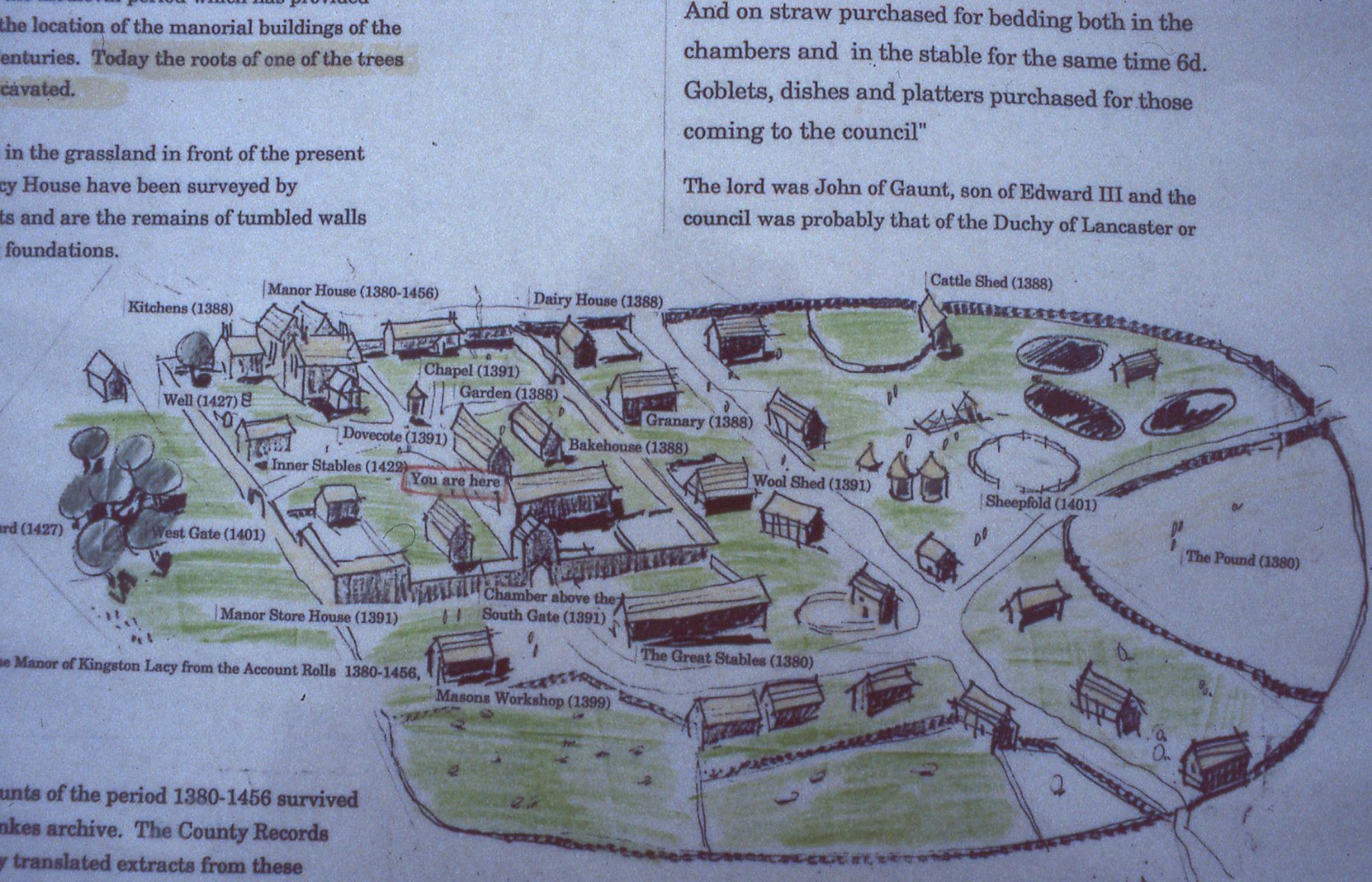

The oldest part is the 14th century chapel. The adjoining 15th century hall has an open oak roof with wind braces decorated with intricate carving. The manor house was refurbished in the 16th century and has the appearance of a Tudor house, added to and then converted to a large farmhouse in the 18th century.

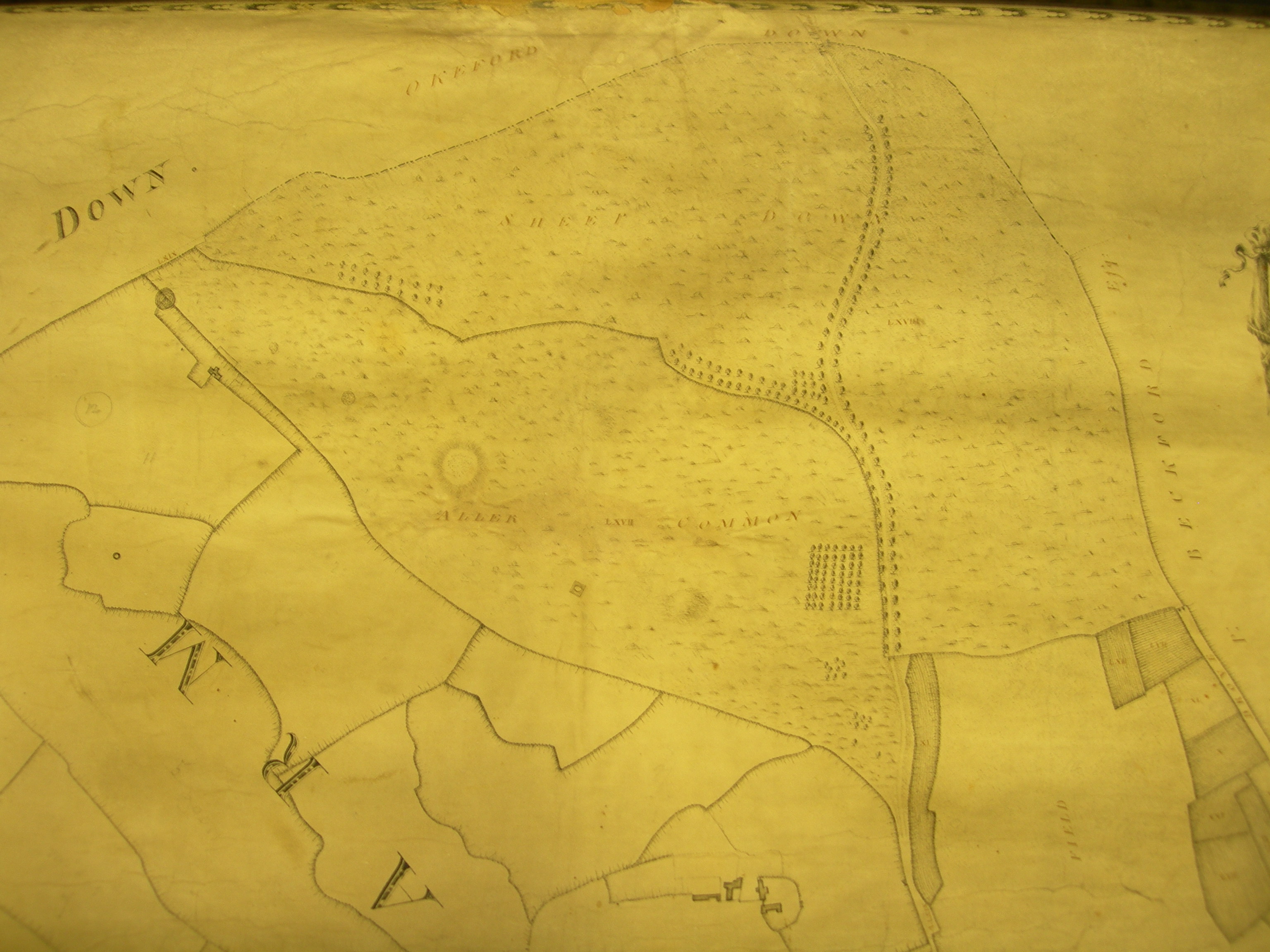

The pasture land to the west is covered with earthworks which represent enclosures and building platforms, the remains of the deserted medieval settlements of Tuckers and Cooks Cary.

Cary is the name of the river and Lyte is the name of the family who held the property from the medieval period.

The house became neglected, and by 1907, when Sir Walter Jenner purchased it, the medieval hall had been turned into a cider store. Sir Walter’s brother Leonard had already purchased Avebury Manor in Wiltshire and both renovated their properties and made them into family homes. Lytes Cary was given to the National Trust in 1948.

Both houses include distinctive Edwardian architecture as the brothers shared ideas as they renovated their homes. At Lytes Cary, there is an Edwardian water tower in the grounds, built in the shape of a medieval dovecote, a copy of the dovecote at Avebury.

This year, Mark, the NT Area Ranger, contacted me to say that he would like to make some wildlife ponds to improve wetland habitat for Great Crested Newts. Two at Montacute, one at Tintinhull and two at Lytes Cary.

I checked the proposed sites against our archaeological records. None of the ponds would cut through anything we knew about.

However, this was an opportunity to look beneath the soil in an area rich in history so I asked for an archaeological watching brief to record anything that was unearthed.

Pete agreed to visit and record any archaeology at each pond ..but also, on this occasion, the excavations were checked using a metal detector and Josh volunteered to do this.

The archaeologist found nothing significant but Josh found a pink rusted Rolls Royce at Tintinhull Pond…. which, may once have belonged to Lady Penelope, famously driven by her chauffer Parker.

The other ponds had finds of old nails and buttons, also a George V penny..

But ..within the spoil excavated from one of the Lytes Cary’s ponds… came a 1/2d of Henry III, then two pennies of Edward I and then a penny of Henry III. Josh sent me his GPS plots of each of these finds which showed that they all lay within a hundred metres of each other.

How unusual.

In the 10 years we excavated at Corfe Castle, we only found a couple of medieval coins. It appeared that the pond excavation had disturbed evidence of a scattered late 13th to early 14th century hoard.

Had someone, 700 years ago, walked down to the river from the now deserted settlement of Tucker’s Cary and… for some reason, buried these coins? Perhaps modern ploughing had disturbed only the upper part of this deposit.

The situation justified the issuing of a rare archaeological research licence to include geophysical survey and metal detecting.

The research design was written and agreed and a few weeks later we assembled in a courtyard beside some modern farm buildings near Lytes Cary Manor House.

A cloudy but warm late March day with buds beginning to explode from the hedgerows; the fields harrowed and the crop beginning to sprout. Mark, Josh and I took a footpath down to the new ponds near the river.

Keith came to help lay out the the grids and we set up the earth resistance meter. Metal detector and geophysics working together. Josh walked up and down the survey grid and began to get signals. The resistivity reading numbers fluctuating up and down suggesting buried walls ….perhaps.

Each find was given a number and plotted to create a distribution map. A blob of lead, an iron nail, a brass button… a tangled strip of bronze, another nail… the day wore on.

Nobody disturbed us in our flat Somerset field, the overcast day gave us a sense of being set apart .. for a time, part of some other world .. we plodded up and down. The finds became less as we moved away from the pond into the centre of the field.

Our next row of grids took us back to the pond. Josh got another reading… a lead musket ball. A strong signal turned out to be a plough share another turned out to be a horseshoe…

A strip of high resistivity signals suggested something solid under foot and every now and then we saw large stones, sparsely scattered across the field. No pottery..no carved or shaped stones… nothing vaguely medieval.

Then Josh found a coin.

It was a William III shilling. We plotted, labelled and bagged it.

I told the story of the lead forging mould I had found in the loft at Lodge Farm, Kingston Lacy. Someone had been knocking out fake shillings there in the 1680s. This Lytes Cary coin was a real one though….but made long after the 13th century.

Josh showed us where he had found the coins around the newly excavated ponds. He gave the area another scan and got another signal in his earphones.

He came across a tiny scrap of metal.

It was a Henry III 1/4d.

Back then, a farthing and a halfpenny were really made by cutting a whole penny in half or into quarters. The back of each coin had a long cross on it and you simply cut it up along the cross lines.

Though we searched carefully…. that was the only medieval find of the day.

We wandered back to the car… satisfied that we had done our best. Perhaps Josh’s finds were just a few coins in a leather purse mislaid one day c.1300.

Later in the week, I downloaded the geophysical survey data. A clear pattern of light and dark on the plot but they were erratic bands. No regular, sharp rectilinear arrangement. No evidence for a long forgotten demolished medieval building. Just a nice geological plan showing outcrops of blue lias stone.

Oh well… you win some … you lose some.